of recent weeks, Dr Erwin Viray (most of you archi peeps would know who, Head of Year One NUS School of Architecture for those who don't) was invited to write an essay on educating architecture in the Asian landscape for a ETH publication (yeah you can go google ETH now if you still dunnoe where it is). He needed some student perspective on the matter, feeling that it was more accurate and in some sense authentic to display how a student would describe his experience in his first year in school, so i was fortunate to work with him on this conversation piece of which he has allowed me to blog on. Its quite fun lah, writing such stuff but yeah its abit long and qhimmed so apologies if you start to feel sleepy, the comments i got was that it was rather long, but some parts are really interesting!

Words in bold are by me (or you can tell by the unpoetic-ness of mine and the super power flower language of his)

We see the world with our eyes. Our eyes mark the shape of our worlds.

I have been watching Japanese television dramas about high school students. The lectures are never shown. The scenes unfold in between the life of the students: in the corridors, in the shopping malls, in their homes. As I reflected on these, I recall movies by Yasujiro Ozu. I recall the placement of the camera on an eye level that is the eye level of a Japanese person sitting or more precisely kneeling on a tatami mat. The camera is unmoving, the scenes unfold infront of it, actions happen beyond the frame. I recall the experience of entering a two mat (tatami) Japanese tea room, with the ceiling that is almost touching my head. As I was standing it felt cramped and low. But as I sat down on the tatami, the space felt right. My eye-level, as in Ozu’s camera could see a another view of the world.

Concurrent with these peregrinations, I imagine the Asian Landscape, so vast and so diverse. Perhaps, so distinct from Europe, even the idea of the unity of Europe in its diversity explored by Jose Ortega y Gasset.

What is an Asian Landscape through the frame of learning architecture? As a teacher, one posits that pedagogy is premised to the universal idea to equip the student with the skills necessary for the practice of a profession, and to enable the student to develop powers of selection by his/her own powers of judgment. Students as individuals have their own eye that maybe is different from my own. And so, I would like to see what they see. I asked Jonathan Lin former year one student at NUS Department of Architecture:

How was year one studio?

First year studio consisted of acquiring knowledge and insights into a relatively new subject for freshmen. I would say that during that period one would learn what most architecture students in other schools learn too, basic foundations that run consistent in any school in any region. Studio sessions involved learning drafting, applying site/contextual analysis and understanding materiality. Studio was also about development, acquisition of knowledge which naturally led to its application to projects. Design task was focused on actual sites in Singapore and was extensive in testing a student's ability to assimilate what one learns into his own individual product. To put it simply everyone receives the same education but through his own context generates his individual design.

The formative period in a studio environment allowed for interaction with tutors and fellow freshmen. Along with the various influences beyond curriculum (Architectural websites, journals and personal field trips) one then begins to develop individual working techniques and methodologies. While working on projects one can test out such technique and assess refine and hone his "style". "Style" among the first years does not just refer to an aesthetic but is more of a slang that refers to an approach to things, to design, to analysis and sometimes even odd sleeping hours (of which all architecture students would understand). Our tutors often encourage us to "go out and see the world", reason being to gain experience and broaden our views, not just to understand what is happening outside but also to appreciate and have better understanding of our own environment. It allows a student to place himself in the bigger picture of things, personally my mission in travelling the entire south east Asia would allow me to better understand the multi cultural environment I live in that is Singapore. Personally I felt that this was essential to becoming an architect in such a melting pot of a context.

what is like to do treetops at the Istana park?

Being presented with a real project that had to be constructed and presented to the public was like throwing us into the deep end of the pool. We were removed away from our comfort zones, away from the safe environment of studio work. The idea of actual construction and scheduling, meeting up with various clients, contractors and authorities although scary was exciting. Filled with enthusiasm, we could finally experiment on new ideas in a real world rather than only in context.

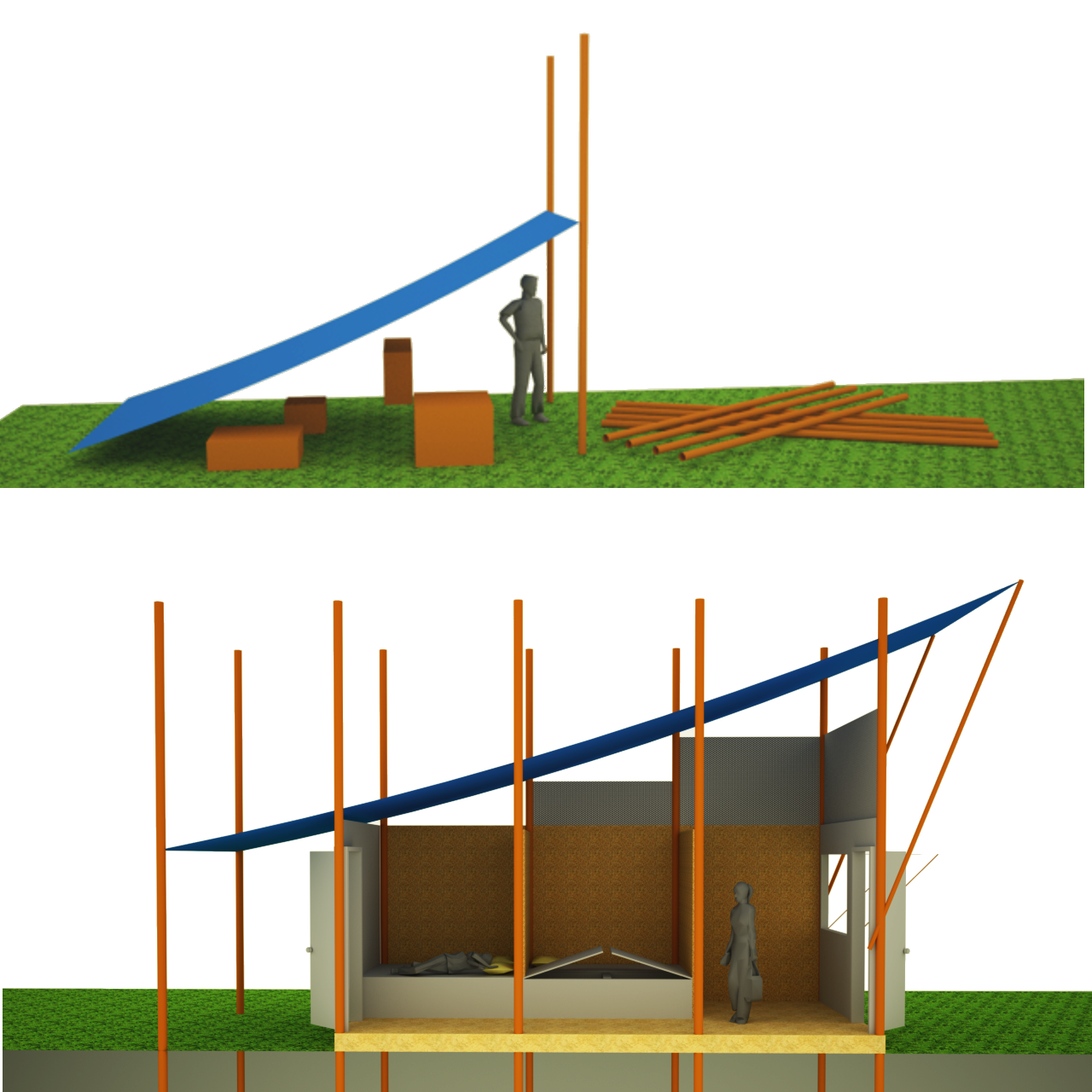

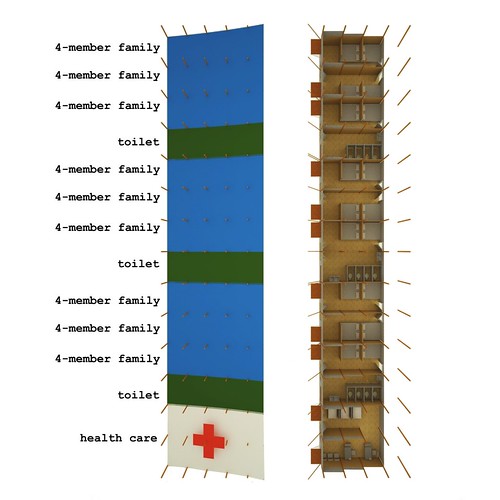

With a free rein where tutors would have minimal intervention (only taking the role of advisor rather than teacher) we had to form our own organization and work schedule, adopting our own approach to the project. Since it was held during the term break, the main aim was to have fun while learning, enjoying the freedom in designing and seeing through a real project. Meetings among us were casual, no hierarchy, everyone had a say to the design and experimentation was key. Paradoxically the real world constraints of such projects provided us the chance to figure out new ideas that weren't taught. A tight budget paired with minimal construction experience among the team members forced the students to go beyond common and costly materials. Accordingly, the idea of deriving a form and then developing a construction strategy was also thrown out the window. Modeling and form making focused on the construction technique rather than final form, with the idea of ease of construction and temporary structures.

Constraints such as minimal digging on site forced students to think beyond conventional ideas of foundations. The pavilion would have to be made of light materials that provided adequate shade from the sun and also provide create an interactive play area for children to explore the park. An open stilt structure that gains in strength its seemingly random arrangement of beams and a maze made of recycled wood that occupies a large portion of the site. The building is baseless and users would walk on the grass right into exhibits which are under a light cloth canopy. A maze forces one to make turns, constantly shifting views, allowing him to experience the vastness of the park in a fresh perspective. From afar an image of a light and open building is created, children would be playing in and ON the maze as each maze component is not fixed into the ground but can be reconfigured to their fancy.

The team realized the need to change the design and sometimes even the conceptual ideas to see through the whole project. Compromise? Maybe but what we can call it is a rigorous review and correction of our ideas, that not everything we do is always right in the eyes of the client, public. We no longer just have tutors to review us, it is an added dimension that classroom projects just do not provide.

Final construction and opening of the pavilion to the public was a new experience for the entire team. With only three days of construction, we worked with tight schedules that relied heavily on good teamwork and management. Early mornings and hot afternoons weren't favorable but with everyone wanting to see through a project they have all worked on for three months, there was a passion to complete what we started that would probably not been seen in any studio condition.

Jonathan’s words provide a picture in an Asian Landscape of architectural learning. Seeing these words, I reflect on what Jose Luis Mateo stated regarding the studio at ETH Zurich as a stage set, where the student is given the world to face unexpected things in order to formulate questions and find answers. And the teacher’s role is to help set the students in finding the correct answers. Elia Zenghelis’ contributes the importance of imparting to students the basic knowledge of the discipline. It is crucial that the students know the facts: the dates, the names, etc, in order to be able to form their own judgment and make their choices for contemporaneous response to contemporary needs of life now. At the Architectural Association in London, Anthony Vidler shared the importance of History, saying that the most interesting and brilliant practitioners of architecture are also very good historians.

From these words, I see no difference in the aim to define approaches to architectural learning. In parallel, I asked is there a difference in the mentalscape that guides the forms and configurations in a particular geography functions? Michel Foucault in the preface to “the Order of Things” credits Jorge Luis Borges’ passage as a passage that shattered all the familiar landmarks of thought, “our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography – breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten with collapse our age-old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes a ‘certain Chinese encyclopaedia’ in which it is written that animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.’ In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that.” It is a lucid, humorous, and quite disturbing passage on how the world is seen through our classification of the world citing Chinese things to set the stage on ordering of seeing the world. It is most possible that, ‘Chinese thought is something that never construct a world of ideal forms, archetypes, or pure essences that are separate from reality but inform it. The whole of reality is seen as regulated and continuous process that stems purely from the interaction of the factors in play. ‘ Things can rely on the inherent potential of things or the situation or configuration of things, that we may call the practice of the efficacy of things, based on the propensity of things. It is perhaps the lesson of the Japanese drama, and the treetops at Istana Park and this text that we now read.

In ‘Immemory’ Chris Marker would say, ‘A more modest, but also more useful, enterprise would be to represent each memory with the tools of geography. In each life, there are continents, islands, deserts, dams, overpopulated countries and unexplored territories. In memory we can represent maps and landscapes more easily (and more precisely) than songs or stories.’ This text is an attempt, a composition to describe and present a landscape of a certain memory, in a certain place and time, crafting a landscape of learning Architecture. In this text, an attempt to create an archive is tested, our world of classification is examined to paint one face of an Asian Landscape that may not be so different from Other Landscapes of learning architecture.